Liberating data with FOIA, part 1

- This post first appeared on the Cornell Tech DLI 'Critical Reflections' blog.

After leaving a previous role as The Verge’s senior privacy and cybersecurity reporter I was looking for a chance to pause, catch my breath, and explore new areas. A fellowship at the DLI was a great opportunity to do this, and after having moved on again towards the end of 2023, I’m reflecting on the various topics I was able to dive into in a year at Cornell Tech.

The three main areas I covered in this time were FOIA law as it applies to data; applications of AI for investigative journalism; and improving my grasp of JavaScript with a view to building news applications.

Here I’m going to dive into the first area, in what will be a two part series. In part one we'll start with principles for identifying government databases, then explain the mechanics of a specific FOIA request in another post.

Applying FOIA law to data

Bringing previously unreleased documents to light through FOIA is an exciting part of journalism, but the process of actually obtaining them can be fairly dry. One of the things it takes is an understanding of the different agencies and departments that make up the government; along with a rough mental model of the different types of records these agencies produce, and enough curiosity, motivation, and persistence to request them.

At about the time I decided to sharpen my skills in the above areas, I heard about a new initiative from data journalist/editor Jeremy Singer-Vine, called the Data Liberation Project.

Singer-Vine is widely known in data journalism circles thanks to his Data Is Plural newsletter, a weekly collection of “useful/curious datasets” running to more than 350 installments at time of writing. The Data Liberation Project — DLP for short — is an extension of this work, but with a shift from curation to investigation.

Rather than catalog what's already public, the goal of the DLP is to "identify, obtain, reformat, clean, document, publish, and disseminate government datasets of public interest." That means filing public records requests with governmental agencies and publishing any data received along with the text of the correspondence that helped obtain it: an open-sourcing of the process and results that can serve as a useful point of reference for others hoping to undertake similar work.

I reached out to Singer-Vine about the project and he suggested we could jointly file a request. In theory there was an upside for both of us: I could learn from a deeply experienced collaborator, and in answering my questions he could keep refining his approach to FOIA education — feeding back into the DLP’s knowledge-sharing mission.

We ended up filing a joint request in March of 2023 which eventually liberated some previously undisclosed data a full six months later, in October of the same year. Here are some of the lessons I took from the process, drawn from notes I made along the way.

Where to find government databases

The government collects a lot of data. Over time, thanks to campaigning, legislation, and the internet, there’s been a trend of more data being made available through open data initiatives like Data.gov, but that by no means implies everything of public interest will be made public by default.

If we’re talking about data in a general sense – individual records, reports, and so on – then sites like FOIA Wiki do a great job of explaining how to find and request them. But I was interested in following the approach of the DLP, which focuses on finding and requesting datasets from the government that can then be analyzed with the tools and methods of data journalism.

So, how does one identify datasets and databases maintained by government agencies? Firstly, by knowing what information agencies must disclose about their data collection practices, and where these notices will be posted. From what I learned there are three key sources:

1. Privacy Impact Assessments

In the US, the E-Government Act of 2002, Section 208, created a requirement for agencies to conduct privacy impact assessments (known as PIAs) when they collect personal data to input into electronic information systems. Many agencies make these available in a distinct section of their governmental website — for example, here’s a nicely formatted list of PIAs uploaded by DHS’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA).

So one place to start is by visiting the website of a department or agency with jurisdiction over your area of interest, and browsing or searching for PIAs published there to see if any of them hint at the existence of a compelling dataset that is not yet public. (The question of how to know what makes a dataset compelling and/or newsworthy is a key intuition to develop as a data journalist, but is outside the scope of this blog post…)

2. System of Records Notices

PIAs are useful, but they’re not the only way that agencies signal an intent to collect data. Thanks to the Privacy Act of 1974, government agencies are required to post notices about “systems of records” – broadly a synonym for databases, though encompassing offline filing systems – in the Federal Register, which is the journal of the government of the United States.

In fact, there’s a whole category of entries in the Register known as System of Records Notices (SORNs), and searching for “system of records” plus an agency name usually brings up many references to government databases. (There’s also a dedicated page just for Privacy Act notices.)

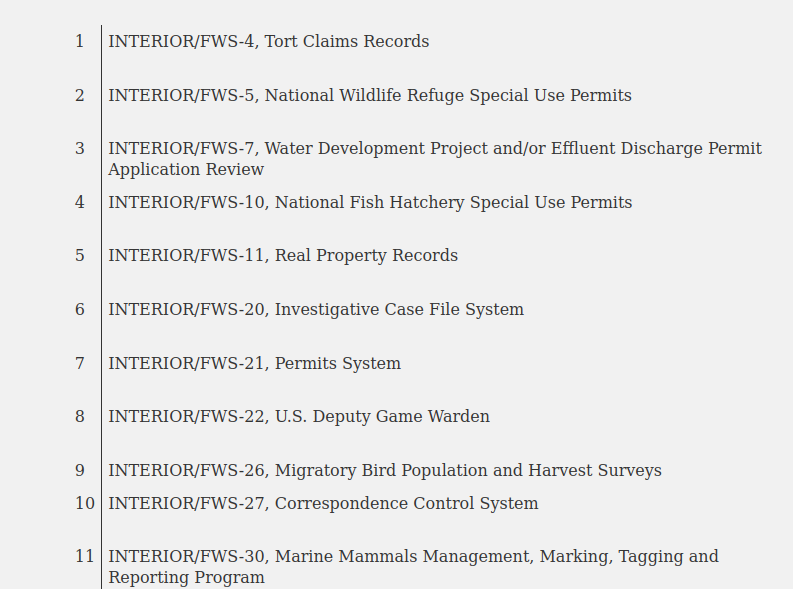

Finding these notices can be very helpful for framing a FOIA request because the notifying agency will identify the system of records by name and explain its purpose. For example, in this March 2023 notice, the Fish and Wildlife Service details its intent to modify 11 of its current systems of records to add a procedure for responding to data breaches. After the summary of the notice, all 11 of these systems are identified by their official designation and usage:

With these details published, SORNs in the Federal Register are a great way to find out about government databases. They can be found via search engine too without visiting the Register: a basic search of “[Agency name] SORNs” is often enough to bring up a page on the relevant agency’s website, e.g. the top result for “Department of the Interior SORNs” is this page:

One thing to take into account though: not all government databases are covered by the Privacy Act, as some are deemed not to contain any personal information that is subject to privacy law.

3. Information collection requests

SORNs are good for getting a high-level overview of government information systems, but for a more granular way to see what data agencies are gathering we can turn to information recorded by OIRA, the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs.

OIRA was created by the 1980 Paperwork Reduction Act (PRA), a law governing how federal agencies collect information from the public. The aims of the PRA are to avoid burdening the public with unnecessary information requests, and to make sure that data collected really is a good fit for its proposed use. What this means in practice is that when agencies wish to collect information from the public, they must first get approval from OIRA by submitting a request.

OIRA has a website, reginfo.gov, that holds information about all of the different information collection programs that have been submitted to OIRA. It can be a little difficult to navigate, but there’s a page that lets you access an inventory of all currently active information collections, and a search tool with many different options to search by agency, sub-agency, date of request, and other details that collecting agencies must supply such as estimations for the number of respondents and time/cost burden for those who will respond to the survey.

With the OIRA search function you can select an agency and sub-agency of interest – a great help if you have a general area of interest in mind – and filter by requests that are currently active.

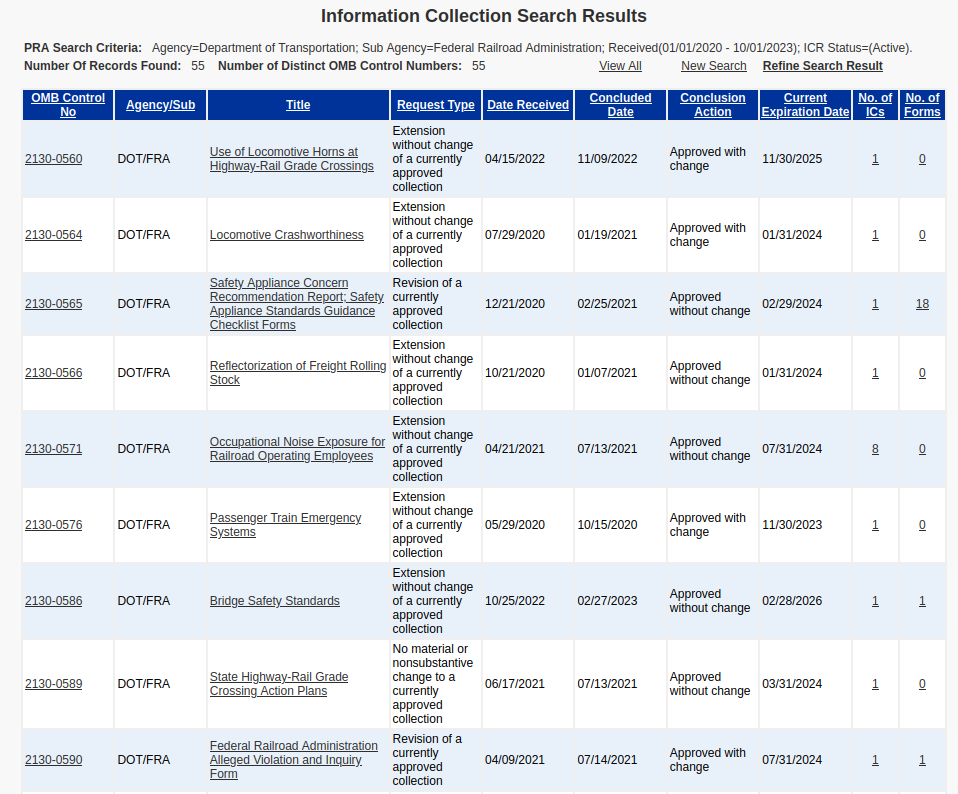

As an example, running a search on ICRs coming from the Federal Railroad Administration turns up a list of responses that point to data that could, if obtained, potentially form the basis of a news story: from the crashworthiness of locomotives, to noise exposure for railroad employees, to railway bridge safety standards, and more.

So: having found a reference to a relevant database, data collection project, or system of records through one of those three sources – now what?

The short answer is that it’s time to craft a FOIA request to ask for records contained in the system. The longer answer is that specific wording might be needed to receive these records in a format suitable for data analysis, which we get into in part two of this blog series.

In the meantime, all of the Data Liberation Project’s previous records requests are online if you’re looking for inspiration, and more information about the sleuthing process is available in the DLP’s Fathoming Federal Data guide.

© Corin Faife.RSS