Learning GitHub Actions (and actually learning)

Docs and debugging > ChatGPT

I’m working on a project for AFP that involves pulling data from an API on a daily basis, and storing that data at a URL online so that it can be read by another application.

There's only a small volume of data and I want the system to be maintainable by people with a lower level of technical skill than me, so rather than provision a server and/or database, I'll be using GitHub Actions to automate a script that fetches data and writes the results to a CSV. This is a pretty common data journalism workflow, but I've never used Actions before so it's a learning opportunity for me.

It's part of a bigger project that took me into some unfamiliar territory with regards to front-end development. I put the web interface together with some help from Claude, and though the workflow was extremely smooth, I was also left feeling that in some areas I'd traded efficiency for education. The process of trying, failing, debugging, and repeating is crucial to getting better as a programmer, and a lot of that gets lost when a language model spits out a perfect solution to your problem.

So this time I avoided AI assistants and learned how to use the Actions platform through the documentation provided and some trial and error, noting mistakes along the way. It was slower, but the sense of learning and reward was greater as a result.

Here are some notes...

Making a workflow

GitHub Actions is an automation platform for application building, testing and deployment. I'll only be using a fraction of its capabilities, but I still need to start by understanding the basic building blocks.

The core of GitHub actions is a "workflow," a bit like a recipe that outlines the process by which a meal is cooked. The GitHub documentation explains that a workflow is a "configurable automated process that will run one or more jobs." Jobs are a set of steps that the workflow executes in order, after being triggered by an event. An event can be an action performed on the repo, like a code push or a pull request, or it can be a scheduled event, which is what I'll need to set up in the future.

A workflow is executed by a runner, a virtual machine that is newly provisioned each time the workflow is run. This means effectively it's starting from scratch: everything required to execute the jobs (languages, dependencies etc.) needs to be defined in the workflow file, as the environment will have to be installed each time.

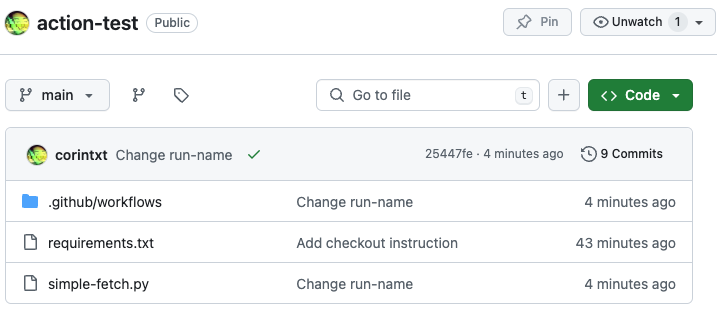

Workflows must live in a directory named .github/workflows/ inside a GitHub repo. The details of the workflow go into a YAML file, which GitHub will use to provision and configure the runner that's going to execute the workflow.

For a first simple test workflow I'm going to use Python requests to retrieve a static CSV file from another GitHub repo and write it out to a data directory, which approximates what the larger project will require at a basic level.

I already found an example of an ETL pipeline that uses GitHub Actions, so I'm going to simplify and adapt some of that YAML config and combine it with GitHub's basic demo example to build a workflow will fetch and save data each each time I push to the test repo.

Learning 1: Check out your code first

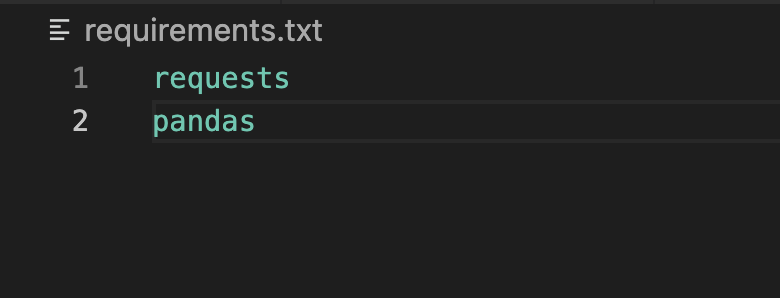

The only requirements I will need are requests and pandas, so I'll add them into a requirements.txt file.

To test this part of the code, I added a YAML file that would install Python and dependencies without running any other scripts.

name: simple-fetch

run-name: Pip install test

env:

PYTHON_VERSION: "3.10"

on: [push]

jobs:

fetch-save-pipeline:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- name: Set up Python

uses: actions/setup-python@v5

with:

python-version: ${{ env.PYTHON_VERSION }}

- name: Install Dependencies

run: |

python -m pip install --upgrade pip

pip install -r requirements.txt

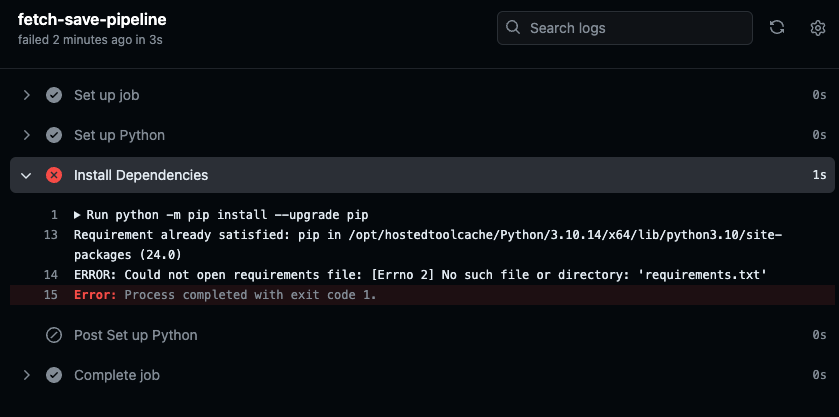

When I committed this to GitHub I got an error that the requirements.txt file didn't exist (though the Python setup succeeded).

At first this seemed confusing, because I could see the requirements.txt file in the root of the repo. But I'd missed an implication of the fact that GitHub Actions have to be built from scratch: for the runner machine to have knowledge of any files in your repo, you need to explicitly tell it to check out the code from the repo first.

I modified the YAML file to include this instruction:

...

jobs:

fetch-save-pipeline:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- name: Checkout code

uses: actions/checkout@v4

- name: Set up Python

uses: actions/setup-python@v5

...

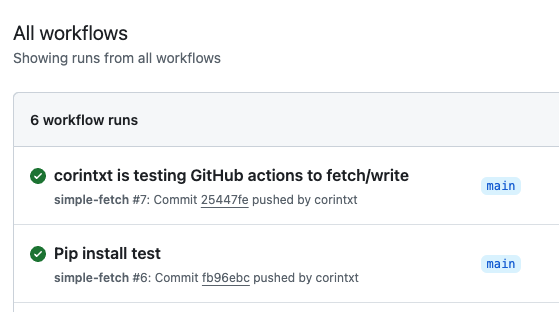

And got a success message this time :)

Learning 2: Commit any changes back to the repo

The next step was to get the data with some Python code and save out the results. I made a simple script to fetch a test CSV file and write it into a data directory, and added a step to run that script in the YAML file.

on: [push]

jobs:

fetch-save-pipeline:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- name: Checkout code

uses: actions/checkout@v4

- name: Set up Python

uses: actions/setup-python@v5

with:

python-version: ${{ env.PYTHON_VERSION }}

- name: Install Dependencies

run: |

python -m pip install --upgrade pip

pip install -r requirements.txt

- name: Run script

run: |

python simple-fetch.py

Pushing these changes to the repo triggered the action to run again. Another success!

Then another confusion: when I ran the script on my laptop, it created a new directory called data and output a CSV file there. My GitHub workflow executed the same script successfully, so I expected to see the same directory and the output data in my main repo. But...nothing :(

I'd missed another important step: to modify the contents of the repo, the workflow needs to be instructed to make another commit. This seems obvious in retrospect, but I had been imagining that the relationship between GitHub workflow and GitHub repo was something like the working directory on my local machine (not so).

Learning 3: Specify git config

So, commit the changes. The first commit I tried failed because I didn't specify the git username and email to associate with the commit – again, necessary because everything is being set up from scratch each time.

Learning 4: Set permissions

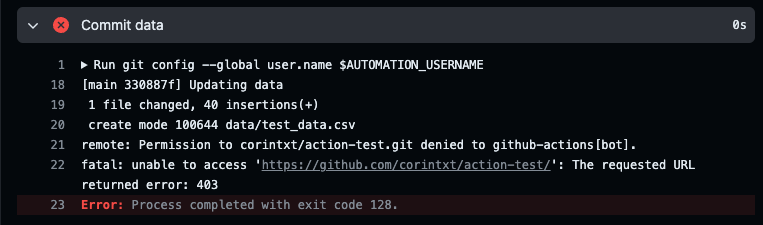

I added a username and email to the config and tried again. Then, the commit failed because of insufficient access permissions:

After consulting GitHub's documentation for assigning permissions to jobs, I added a new line in the YAML granting the fetch-save pipeline permission to write to the contents of the repo:

on: [push]

jobs:

fetch-save-pipeline:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

permissions:

contents: write

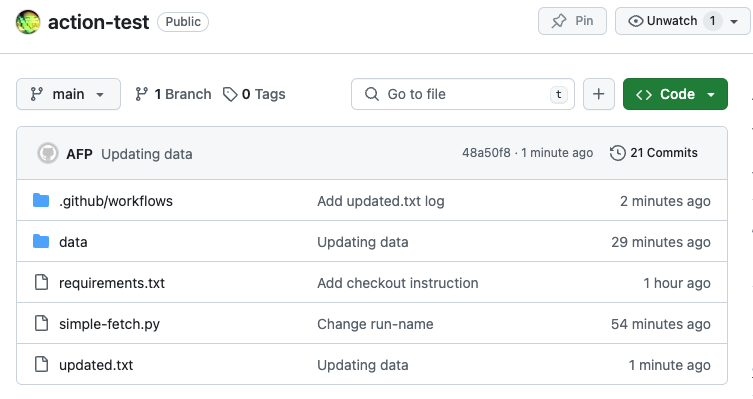

I also added another simple step to log the date and time of the most recent update into a file called updated.txt. (I'll want to do something more sophisticated in a production application, but establishing the general principle is fine for now).

- name: Log last update time

run: |

date > updated.txt

Now it works! The data is fetched and written into a new directory, with the update time in the updated.txt file.

The final workflow YAML file looks like this:

name: simple-fetch

run-name: ${{ github.actor }} using GitHub actions to fetch/write

env:

PYTHON_VERSION: "3.10"

AUTOMATION_USERNAME: "AFP Automation"

AUTOMATION_EMAIL: "automation@afp.com"

on: [push]

jobs:

fetch-save-pipeline:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

permissions:

contents: write

steps:

- name: Checkout code

uses: actions/checkout@v4

- name: Set up Python

uses: actions/setup-python@v5

with:

python-version: ${{ env.PYTHON_VERSION }}

- name: Install Dependencies

run: |

python -m pip install --upgrade pip

pip install -r requirements.txt

- name: Run script

run: |

python simple-fetch.py

- name: Log last update time

run: |

date > updated.txt

- name: Commit data

run: |

git config --global user.name $AUTOMATION_USERNAME

git config --global user.email $AUTOMATION_EMAIL

git add .

git commit -m "Updating data"

git push

Even with some reference examples it took me a couple of hours to get this right from start to finish. None of the sample workflows had exactly the combination of steps I wanted to use, so I still had to fix various problems along the way.

Yes it felt slow, but I know that I learned something. A nice reminder of the value of figuring things out.

© Corin Faife.RSS